Issue #62: Belonging and Accountability

"...true accountability is changing your behavior so that the harm, violence, abuse does not happen again.” — Mia Mingus

This summer’s semi-hiatus lasted longer than expected. Although I could blame my absence on the sudden-to-me resumption of work travel, in truth, I’ve avoided writing because I’ve been scared to write about today’s topic of accountability.

Here were my initial thoughts:

American mainstream culture of individualism and hierarchies falsely equates accountability with punishment and builds carceral systems to define who and what is accountable on the basis of separation and domination. After over two years of exploring belonging, one of the meta-shifts necessary for cultivating belonging is moving from toxic individuation to collective liberation. The United States mythology and exercise of freedom assumes individuals deserve to make choices that are free of consequences for self and others as long as those consequences can be separated from existence. But this fairy tale belies the nature of our interconnectedness. In other words, moving from transactional to relational ways of being and living recognizes that our social relationships are required for survival and flourishing. And like any other living organism, our relationships experience “illness” and “injury” that arises in times of conflict. Much like biological illness and injury are simply part of living and being human, our relational illnesses and injuries are also natural parts of our existence and accountability is a medicine or practice that we can use to treat these conditions.

Viewed in this light, accountability moves from a destination or outcome to a journey toward return and regeneration. It also moves from the punitive frame of victim vs. perpetrator comprising the criminal justice system and embedded throughout our political economy and culture. Accountability provides validation and acknowledgement that boundaries have been crossed and prompts contrition. The practice of accountability serves as a sign of hope for repair and creates a path for making amends to restore the health of the relationship(s). Activist Mia Mingus outlines four parts for accountability: “Proactively taking accountability for our actions is an important way we can build trust with the people in our lives. It is a practice that demonstrates our character, integrity, capacity for self-reflection, and the kinds of values that we are committed to. It is a practice of interdependence, a way to care for those we love and our selves, and shows that we have done our own internal work to take responsibility for our actions.”

In a society where toxic individualism pervades, punishment is able to masquerade as accountability through fear. Rather than self-reflection, acknowledgement of harm comes from individuals and individuals with power over others without consent or care. This acknowledgement is encoded in criminal law but can also be revealed by what is exempted from criminalization. For example, jaywalking and shoplifting that bear criminal enforcement while wage theft and rampant civil forfeiture are not viewed as harmful.

Rather than apologies to rebuild broken trust, punishment demands suffering at or above the perceived level of harm. After decades of justifying an outrageously large criminal justice system, the most robust criminological meta-analysis conducted to date concluded the following:

“Based on a much larger meta-analysis of 116 studies, the current analysis shows that custodial sanctions have no effect on reoffending or slightly increase it when compared with the effects of noncustodial sanctions such as probation. This finding is robust regardless of variations in methodological rigor, types of sanctions examined, and sociodemographic characteristics of samples. All sophisticated assessments of the research have independently reached the same conclusion. The null effect of custodial compared with noncustodial sanctions is considered a “criminological fact.” Incarceration cannot be justified on the grounds it affords public safety by decreasing recidivism. Prisons are unlikely to reduce reoffending unless they can be transformed into people-changing institutions on the basis of available evidence on what works organizationally to reform offenders.”

Where punishment serves to maintain the status quo of domination, the people-changing that this study calls for comes from all of learning the skills and practices of accountability to build institutions, communities and systems that enable relational cultures that enable public safety.

Punitive culture manifests in overt norms like respectability and professionalism and more covert norms like white victimhood that often deploy a rhetorical strategy/framework that Professor Jennifer Freyd has defined as “DARVO”: "Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender." Punitive institutions rob people of dignity and personhood as they are forever marked as deviants and beyond redemption, a philosophy that runs counter to most world religions. Punishment assumes the existence of natural hierarchies that require protection and maintenance of moral purity that relegates naturally deviant people into conditions of suffering deprivation. One example of this moral judgment and purity arises in the widespread use of Moral Reconation Therapy.

By moralizing innate character, punitive culture allows institutions and systems to evade accountability for the harm and violence of broken relationships and impede repair. In this context, authentic expression of feeling and naming become powerful countermeasures to enable accountability. The mosaic of the world’s reactions to the Queen of England’s death provoked intense reactions and feelings among royalists and colonized peoples over the impact of the past and who and which institutions ought to bear accountability and what acts they are accountable for. Contested histories serve as cracks in armor of punitive cultures that allow accountability to grow roots.

While naming and authentic expression of emotion are necessary for the transition away from accountability-free society, they are insufficient for building new practices, policies and systems that make harm less likely and repair more available. Ultimately, changing behaviors through approaches like collective action and policy change.

After 30 years of parents, administrators and other adults disregarding and dismissing children’s reports of their teacher’s harassment, a group of middle school boys in the Boston area came together in January 2021 to document the teacher’s behavior in a “pedo database” they maintained in a private shared Discord. That documentation finally convinced the administration to remove the teacher after more than a year.

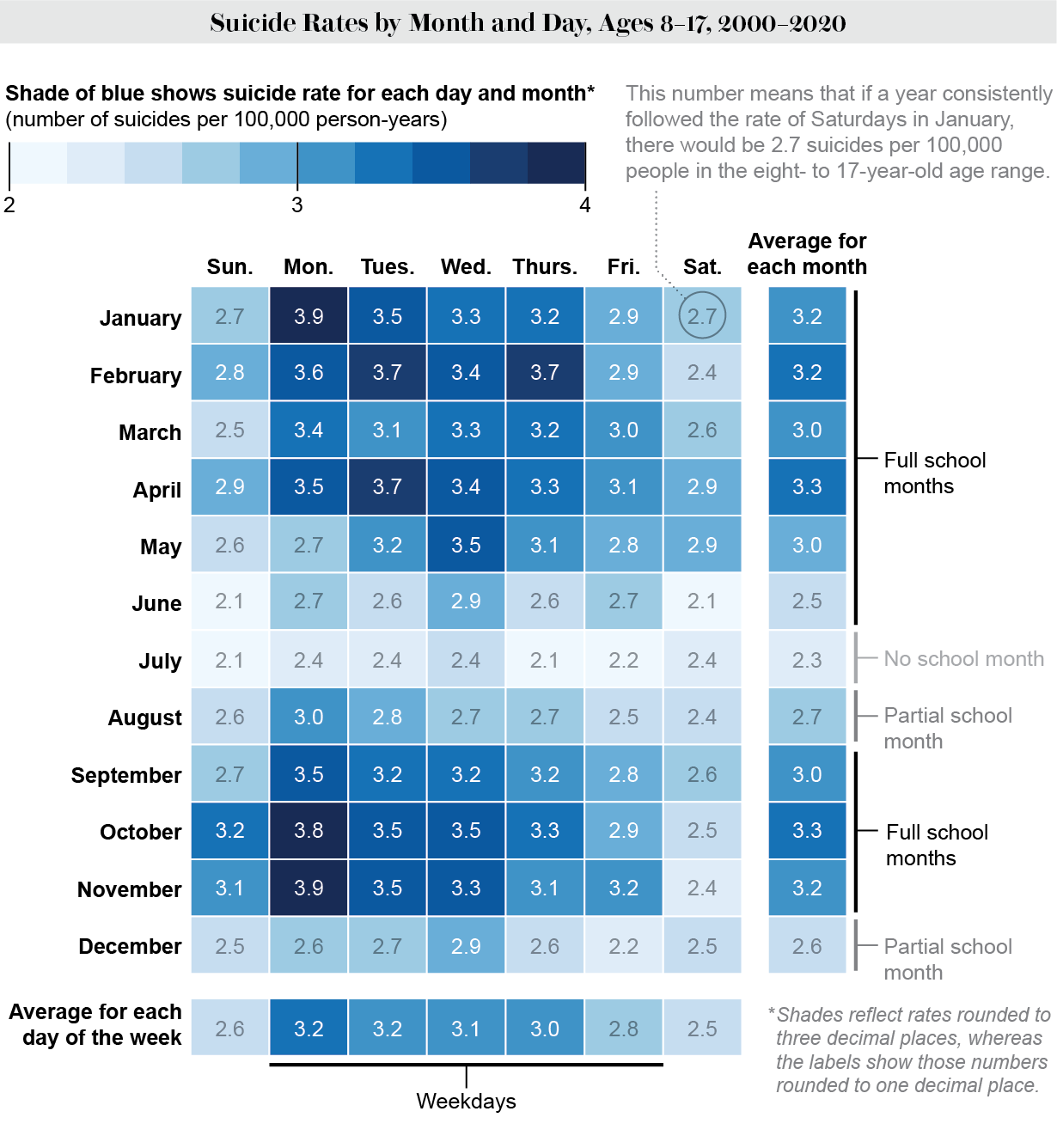

This example underlines how hard it is to change behaviors, especially when considering the behaviors of institutions and the important of having social, emotional and material support to do so. For years, public health data and surveys have documented schools as significant stressors for children under 18 years of age. But a medical researcher finally analyzed and visualized the data to make it clear that for many children, schools expose them to substantial harm that prompts suicidality.

Dr. Tyler Black explains some of the reasons for these findings:

School comes with many things, good and bad. School can be wonderful, with learning experiences, social successes and a sense of connection to others. But it can also be incredibly stressful because of academic burden, bullying, health- and disability-related barriers, discrimination, lack of sleep and sometimes abuse. I often liken going to school to a child’s full-time job. The child has co-workers (classmates arranged by hierarchy), supervisors (teachers), bosses (administrators and principals) and overtime (homework). And they have very early work hours (most schools have hours that are very incompatible with children’s sleep patterns). Of course, work can be rewarding, but it’s also stressful.

Institutions are built to maintain the status quo. If the form and purpose of that status quo upholds punitive culture rather than embracing more relational cultures that support accountability and care, those institutions will squelch internal dissent and resist external demands on change to the detriment of everyone within those institutions who can’t afford to live as though those circumstances don’t exist or don’t matter. When we see institutions move to silence dissent and resist change, we should ask the following questions:

Who does it serve to have these thoughts, feelings, knowledge and/or reactions unexpressed or inaccessible?

How might expression or accessibility contribute to accountability?

Who or what gets to determine who is or isn’t being served?

Abolitionist Ruth Gilmore introduced the concept of organized abandonment: institutional and systemic disinvestment from life-sustaining services and infrastructure such as healthcare, education, and housing with concomitant investment in life-draining services and infrastructure such as policing and incarceration. Psychology professor Jennifer Freyd’s concept of institutional DARVO explains what happens when institutions and systems are held accountable for behaviors like organized abandonment and institutional betrayal.

Being human is hard and practices of accountability are meant to acknowledge that none of us know what we are doing and we will do things wrong sometimes because of that. The universal experience we share of being victim and perpetrator at different times and in different contexts can provide a bit of comfort and a window of all of us together to transition away from accountability-free cultures. Accountability provides material and psychological safety that allows us to embrace the good times and weather the tougher situations. In the future, perhaps we need accountability accommodations like collective bereavement, self-reflective leave, and reparative rites of passage to accommodate the variety of harms on the horizon as collective traumas grown in frequency, complexity and scale, and harm ceases to fit into neat categories.

Upcoming Events

October 12, 4:30 pm PT/7:30 pm ET: Twitter Spaces signals scavenger hunt - Belonging and Accountability

This 30 minute session is a fun way to surface disruptions and innovations and talk through potential impacts and consequences with others.

October 26: October reader meetup

This 90 minute interactive session is an opportunity to dig into futures thinking tools more deeply to create a picture of how belonging might shift over the next decade.

This piece is incredible!