Issue #57: Community and Belonging

“To build community requires vigilant awareness of the work we must continually do to undermine all the socialization that leads us to behave in ways that perpetuate domination.” — bell hooks

Hey!

Welcome back to my current readers! Hello and a warm welcome if you’re new here!

If exploring and examining belonging and the myriad of ways humans relate to each other combined with the imaginative and systematic ways we can envision future possibilities sounds like a cup of your favorite toasty beverage, I invite you to subscribe and share this newsletter with someone(s) you care about.

A couple of weeks ago, I had the great fortune to finally connect with Mia Birdsong, discussing our love and experience of community. Especially amid the COVID19 pandemic, I’ve seen several articles and social media posts celebrating the everyday joys of befriending neighbors and finding connection and resilience in community. In many ways, we took these relationships for granted in the Before Times, making the (re) discovery social ties outside of our most intimate interpersonal relationships one of the bright spots in a difficult time in contemporary life and history. Much like our intimate relationships, community ties require labor and investment to build those connections.

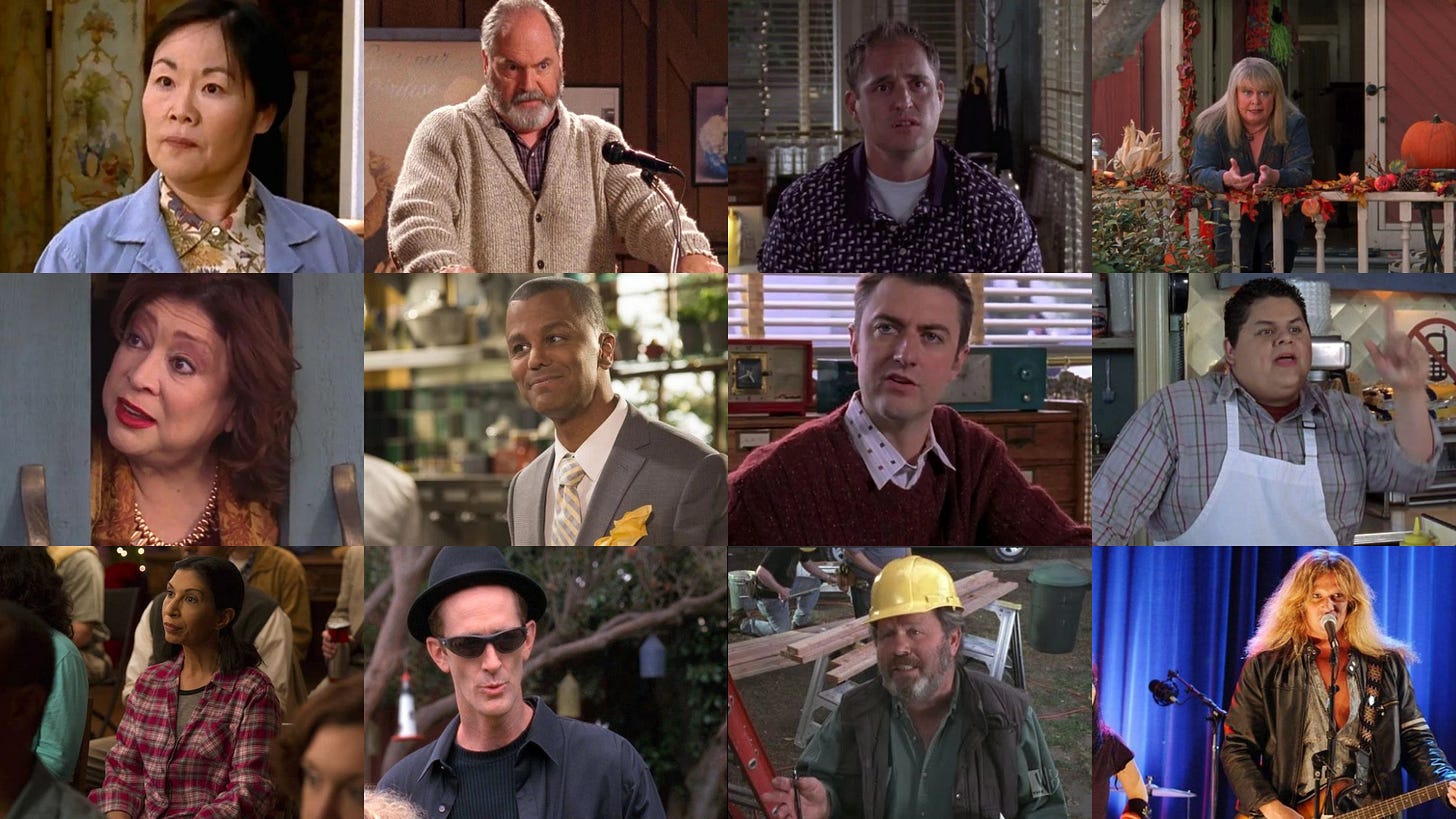

If you’ve ever seen the show Gilmore Girls, you would see that outside of the titular relationships among Lorelei, Rory, and Emily, the show features an array of quirky, borderline annoying personalities in the fictional town of Stars Hollow who all play vital roles in facilitating the main characters’ development. In so many ways, the individual growth of each of the main characters is a reflection of and a byproduct of the community they live in. Each of these secondary characters helps to weave the community of Stars Hollow. Those weirdos include the local diner owner who provides the gathering place for the exchange of information and resources, the overly demanding grocery store owner who’s a bit of a crank but also the keeper of a community’s history, the town gossip and a local business owner always full of fantastical tales of a life well-lived.

I have my own microcosm of Stars Hollow on the block that I live on. My next door neighbors have helped me bring in packages that were too heavy to carry. The two kids who live next door drop by to tell me about school, dance class, and Roblox and to ask for sparkling water and popsicles. A few of my neighbors tend to the community garden on the block, adding a beehive last year so that we all have access to local honey. Others keep me in the loop about new businesses opening in the neighborhood so we can buy more locally.

No matter the approach or differences in personality, the conversation reminded that communities don’t just happen. They are intentionally built and stewarded by official and unofficial community weavers. Whether it’s apartment tenants coming together in a rent strike, or Black families working to reconnect with displaced relatives during the Reconstruction, these community weavers make investments in community that pay dividends in greater sense of wellbeing, life satisfaction, security, and resilience to external shocks.

Because of the stewardship that community weaving requires, it doesn’t scale along similar lines or dimensions as something as mechanistic as a factory. Quality communities need depth of shared history and density of shared interest and openness to engagement, not just quantitative scale. It wasn’t uncommon for me when I lived in the Mission, to see neighbors who never acknowledged my presence, much less knew my name. At its worst, living in that “community” meant my neighbors questioned if I belonged in the building with a passive aggressive “Can I help you?”

There’s a tension between what scale demands and what most, if not all, communities need. Simply put, the strength of community is usually (if not always) weakened as the number of people in it grows. — Why you need to hire a Chief Community Officer (and why "community" and scale are often opposites)

One of the larger questions about belonging that I’ve been thinking much more lately after two years of researching the future of belonging is “Are capitalism and belonging compatible?” In the gold rush of venture capital chasing community as a business model with the hype cycle of web3, NFTs, and the metaverse, I fear that we may lose even more of the belonging that results from long-term relational community weaving and cultivation as the intrinsic rewards of connection are crowded out by extrinsic motivations like social status and cash. These innovations reduce community to bundles of transactions that require that datafication and financialization of all human interactions and behaviors, putting a price tag on every aspect of community.

When I look at the intersection of community and belonging, I see a few positive and hopeful signals:

Rise of the aunties: In many cultures, community weaving is yet another source of unpaid labor often relegated to women criticized as busy bodies, or the old maid next door. The rise of the aunties is elevating the role of these community weavers. Last year, Kareem Khubchandani, a professor at Tufts University, released a call for papers after an online symposium on what he calls Critical Aunty Studies, to examine the social weaving and cultural critique that aunties offer as transgressive figures in communities. Instagram communities like Rich Auntie Supreme celebrate aunties for choosing to live rich lives and “value the added opportunity to show up in various ways to the community around us including nurturing up and nurturing across.”

Growing civic investment in community health: The mayor for the City of London launched the Make London fund invest in community-led projects to aid recovery from the pandemic by supporting community hubs and bringing people together.

Dismantling of faux or illusory communities: In many ways, major social shifts like the Great Resignation are less about specific jobs and more about a rejection of the wide gap between what a job promises in social returns vs. what a job delivered. In the Before Times, the notion of community at work revolved about putting people in physical proximity in offices and other workplaces, and hoping that communities ties serendipitously arose. The pandemic has unmasked illusory communities that actually provide extractive, transactional relationships that undermine the respect, safety, and trust that building communities require.

Leadership development for community weavers: The Aspen Institute launched Weave: the Social Fabric Project to celebrate and build a community of community weavers to better foster healthy, connected communities across the United States. In that same vein, Social Health Labs offers community microgrants of $1000 for any member of the community to step forward and experiment with community weaving in their communities.

Thanks for reading!

I’ve opened paid subscriptions for founding members to join. If you’d like to contribute as a sign of appreciation and support for this newsletter bringing you joy and curiosity, I certainly would appreciate it!

The issues will continue to be free but I’m beginning to design interactive workshops and collaborative visioning spaces for paid subscribers to dive deeper into topics. I’m open to hearing suggestions from you about what you would like to explore and build together with this community of readers. Comment below with your suggestions and requests.

You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here — and you can always reach me at belonging@substack.com.