Issue #18: Imagination and Belonging

“The man who has no imagination has no wings.” ―Muhammad Ali

I’m an extrovert who loves to travel so four months of quarantine life has been pretty brutal. Although I anticipated some of the struggles like loneliness, workaholism, physical inactivity, I got caught flat-footed by the burden of boredom. Some days, I feel trapped, especially after reading the parade of wild news headlines everyday on Twitter. Even though the world around us suffers from overwhelming shock, daily life is drowning in homogeneity and monotony. I simply don’t have enough variety or novelty in the days and weeks, creating an energetic drain and also making the work of creativity and imagination pretty difficult.

If you have ever read Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, one key concept that she advocates is the artist date. An artist date is an appointment that you make with yourself to be by yourself to ensure that you have time and space to explore and play. It doesn’t have to be artsy but it should be something that you enjoy, that may inspire your imagination at a later time. Although not impossible to do in lockdown life, artist dates haven’t been readily available or playful in the last few months.

Imagination is a key tool for futures thinking. By systematically examining the intersection of linear trends and non-linear disruptions, you have the ingredients necessary to imagine future possibilities, worlds and consequences that embody those intersections. In work I’ve done with social impact organizations, we often tell those leaders that the nature of their work makes them futurists. Working to change the world requires you to imagine how things could be different.

As a society, we tend to relegate imagination to the realms of childhood and art. Science fiction is one medium for the imagination of new possibilities. We find science fiction exciting because it challenges us to imagining how science and technology will shape our world. But if you’ve read any science fiction stories or watched any films, you would see techno-centric views of the future. It would be easy to write this off, but what we collectively imagine and consume artistically guides the world that we co-create together. So unless we want to live in a future filled with killer robots that leverage our own apathy and disregard for fellow humans, we need to feed and harness our imaginations to write new stories and narratives.

Social entrepreneur and thought leader Muhammed Yunus called for the creation of “social fictions.”

“We have science fiction, and science follows it. We imagine it, and it comes true. Yet we don’t have social fiction, so nothing changes.” —Muhammad Yunus, Skoll Forum 2013

Imagining social fiction is critical for creating the cultural and behavioral shifts that will foster belonging in the future. We need to provoke ourselves and other members of society to imagine a world free of loneliness and full of connection, a world free of violence and full of safety, and a world free of systemic oppression and full of belonging.

The wonderful thing about imagination? We all have the power to exercise our own imagination in service of building a better world. Famed science fiction writer Octavia Butler broke several rules about who and what belonged in science fiction. She wrote fully formed Black characters into her stories, ushering in the creative movement of Afrofuturism in modern literature. She read the news, academic research and other sources of the written word voraciously in conceiving of her novels. This systematic and broad approach to reading and learning led to the publication of The Parable of the Sower and its sequel The Parable of the Talents, both dystopian cautionary tales advocating for advancing social progress to keep racism from becoming more entrenched. Her books have taken on new life as readers realize her stories predicted the rise of Trumpism, even down to the slogan of “Make America Great Again.”

In Parable of the Sower, when the best friend of the protagonist says, “Books aren’t going to save us,” the protagonist Lauren Olamina responds with “Use your imagination.”

So we are living in the omni-crisis, powerless to fix everything around us and save everyone. But let this be a call and reminder to use your imagination. And not just your imagination, but engaging in collective imagination. In the essay “From What Is to What If,” Rob Hopkins warns of the erosion of collective imagination due to disuse and overwhelm:

“We recognise that if a population isn’t sufficiently nourished, we will see a decline in health and a rise in preventable illnesses. We recognise that if we fail to give a population a good education, it will fail to reach its potential. Yet the neglect of the imagination is generally overlooked, seen as a frivolous distraction from the overarching aim of building economic growth and technological progress.”

He calls for a “revolution of the imagination” to enable the thinking and creativity required for the complex challenges we face. Rather than viewing imagination as a luxury, Hopkins examines the myriad of ways that our systems conspire as a “disimagination machine” to maintain a status quo that keeps us isolated, traumatized and compliant to the very systems that impede belonging by reducing empathy, connection and community.

Kasi Lemmons’ recent op-ed White Americans, your lack of imagination is killing us calls attention to the deadly impacts of this disimagination machine on Black lives in the United States:

Maybe that explains this lack of white imagination: The price of truly understanding black life in America is just too high. That understanding demands too much. If you felt this rage yourself, you would have to acknowledge what caused it, and what it makes you want to do. But while rage can lead to tragedy, it is also a terrible thing to waste. Rage can be useful, necessary even. It fuels our pride and lubricates our resilience. With discipline and unity, rage can change the world. So be enraged with us and for us.

Rather than viewing imagination as a burden, some virtual reality experiences try to show that we can’t afford to not imagine more inclusive world. Dr. Courtney Cogburn, an associate professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work, developed a 12 minute experience called 1000 Cut Journey to show the lifelong experience of racism from childhood to adolescence through adulthood.

Joel Leon draws a through line from the exclusion of Black creatives in history to the lives stolen by police brutality and extrajudicial murders, citing them as “Death by murder of the imagination.” For oppressed populations including African Americans, imagination is not a luxury but rather a death sentence. Imagination is viewed as a powerful tool by those who wield power, and therefore an existential threat when wielded by those lacking power.

Black imagination, by and large, is a rebellion. It is the lit fuse of an already-there powder keg; it is the Molotov, reloaded. It is Harriet Tubman hurrying Black bodies en masse to freedom; it is Nat Turner dying; it is Paul Robeson blacklisted…

Our freedom is inextricably tied to our willingness to reimagine. The imagination is hindered by oppressive structures. How do we imagine when imagination is shackled by the powers that would rather we languish in spaces that do not allow us to be bigger and broader than our current circumstances would allow us to be? Our imaginations can run to places that grant us a freedom the physical world has not yet created for us.

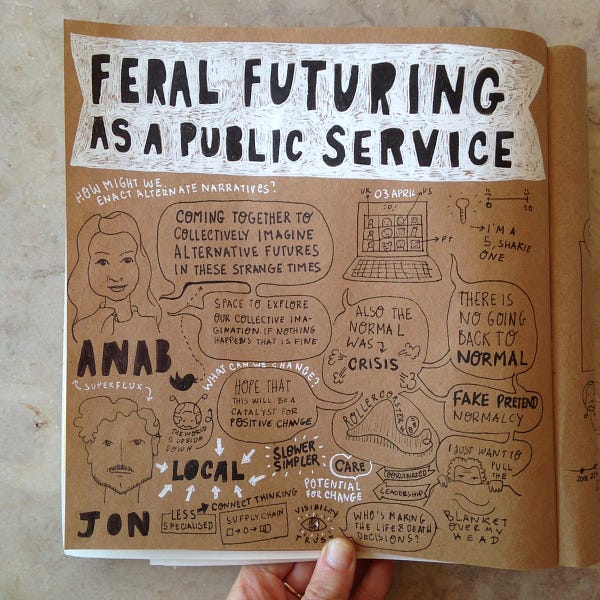

Imagination is more than the story or narrative envisioned when leveraged by people who need it most. It becomes a refuge of safety and the cornerstone of collective freedom and liberation for those excluded. More than a creative exercise, protecting and fostering imagination is an essential service and right in the same vein as food, clean water, and shelter. Anab Jain, co-founder of Superflux, a experiential futures studio, recognized the constraints on imagination in the omni-crisis that we are currently living through. One way through the precarious complexity of our present is coming together to imagine futures that radically reimagine futures in light of our current collective predicament. This “feral futuring” intentionally holds space for coming together for collective imagination that centers belonging even while acknowledging the drag of uncertainty and crisis fatigue and grief. This imagination is a public service to ensure we don’t return to a normalcy that was so harmful to so many. But it calls for new tools to handle the emotional toll of our present to keep the weight from crushing our imagination.

One way that ancient civilization handled crises was in the telling and retelling of mythology. Mythology enables sensemaking by placing events and response to those events in context at a collective level. We can all feel connected and somewhat comforted and safer by knowing that we are not alone in our suffering, grief, and rage, which moves us closer to take action. Myths move the stories we tell from I, the individual protagonist, to We, the interdependent collective.

In This Too Shall Pass, a new report from the Collective Psychology Project co-authored with Casper ter Kuile and Ivor Williams, we look at three kinds of myths that helped our ancestors to make sense of crises that are bubbling up in popular culture once again:

Apocalypse myths – stories in which something is revealed;

Restoration myths – stories in which something is healed; and

Emergence myths – stories in which something is being born.

It is this shift from I to We that will bring about a more inclusive futures of belonging through the exercise of our collective imagination. One way for you to exercise your collective imagination is through the #Imaginable campaign with the Institute for the Future. To participate, share your answers to the question below:

When it comes to the future of belonging, what do you believe must change for us to be happy, healthy, connected and secure 10 years from now?

Comment below with your ideas. You can also tweet them to me (@vanessamason) using #imaginable.

If you can, add links to "signals of change", or evidence that these changes are possible or already underway. These signals are specific, recent, and provocative (ie. surprising, weird, outrage inducing).

Looking for bonus points? Imagine if your idea happens by 2030. What else might happen? Share those consequences as well!

I think we want and we are searching how to build more spaces for talk and for active listening, the sense of community is being built from the links of our stories.